Introduction — the problem in one line

Walkway incidents rarely have a single cause; they are usually the outcome of interacting design flaws, operational loading and maintenance decisions. This article lays out engineer-focused judgment paths — how to identify recurring causes, how to weigh surface repair versus system-level retrofit, and what triggers a change in maintenance or replacement strategy.

Common design failures that raise slip, trip and fall risks

Design failures tend to cluster around four elements: surface friction, drainage and contaminant retention, abrupt level changes, and inadequate edge protection. Each element compounds the others — for example, a slightly low coefficient of friction becomes hazardous when drainage is poor and contaminants accumulate.

Practical red flags to watch for on site: pooling after light rain, persistent oily sheen near process areas, worn or exposed fasteners, and hidden level changes under accumulated debris. When multiple red flags appear repeatedly despite cleaning, you are looking at a design deficiency rather than a housekeeping failure.

How surface geometry and material choices affect real-world slip risk

Friction lab values (COF) are a starting point but not a substitute for field performance. Texture, perforation pattern, and material wear rate determine how quickly a surface loses its effectiveness. In many industrial environments a perforated surface that allows debris and liquid to pass through will maintain better friction than a smooth plate that traps contaminants.

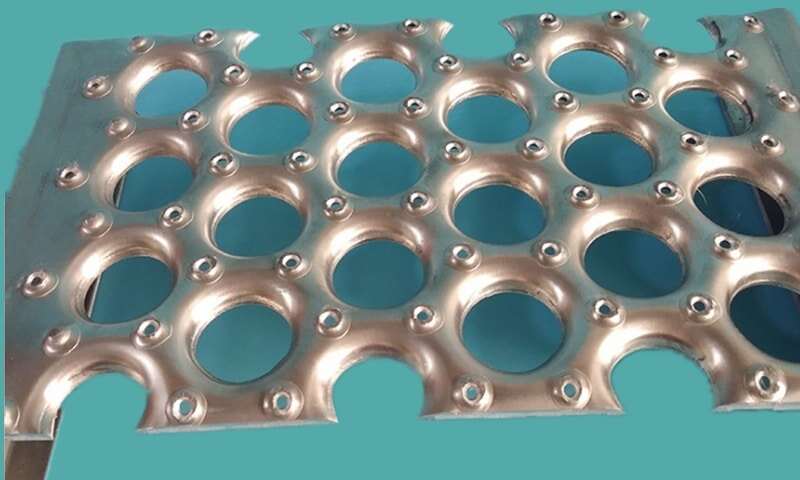

When specifying or retrofitting a high-traffic industrial walkway, consider solutions that explicitly address drainage and contaminate egress rather than only aiming for a high initial COF. For situations where drainage and contamination are concerns, engineers will often specify perforated panels that combine anti-slip profiles with open drainage — for example, using perforated panels that improve drainage and reduce slip risk as part of a layered mitigation strategy.

Drainage, contamination retention and how they drive failure modes

Poorly drained walkways create a persistently hazardous surface even with frequent cleaning. Solids settle into depressions and profile lows, oil forms films over pooled liquids, and biological growth can form in slow-drying areas. The engineering judgment path is to ask: is the hazard intermittent (seasonal spills) or persistent (process discharge, washdown areas)? Persistent contamination strengthens the case for an engineered drainage-capable surface rather than more aggressive cleaning alone.

Design adjustments that reduce long-term risk include increasing open area for drainage, removing low points and horizontal ledges where debris accumulates, and selecting materials that tolerate the plant’s chemical environment. When those changes are considered, it is practical to specify perforated or grated surfaces that allow liquids and small solids to pass through to a dedicated drainage plane. This approach also reduces the frequency at which the walking surface needs hands-on cleaning.

Inspection and maintenance frequency — engineering thresholds to act on

Inspection cadence should be risk-based, not calendar-based. Typical triggers for more frequent inspection include: heavy pedestrian traffic (> X people per hour depending on facility), frequent process discharges, exposure to oils/chemicals, or exposure to freeze–thaw conditions. If inspections repeatedly find surface glazing, embedded grit, or recurring pooling, escalate from cleaning to corrective design action.

A simple decision rule: if the same hazard is observed more than three times within a quarter despite normal cleaning, treat it as a design failure. For such cases, increase engineering intervention — evaluate drainage, edge details and surface open area — rather than continuing to increase housekeeping effort.

Surface repair (band-aid) vs. retrofit (root fix): an engineering decision tree

When choosing between temporary surface repair and a retrofit, weigh four variables: frequency of recurrence, consequence of failure (injury severity, downtime), cost of downtime during retrofit, and lifetime cost of repeated repairs.

- If incidents are rare, consequence low, and a temporary patch significantly reduces short-term risk, a surface repair may be appropriate while planning a scheduled retrofit.

- If hazards recur frequently or potential injuries carry high consequence, prioritize retrofit during the next planned outage. In many industrial plants, that means specifying a walkable surface that combines load capacity, anti-slip texture and open drainage. Where retrofits are justified, engineers should evaluate solutions that both reduce maintenance frequency and simplify inspections — for example, specifying modular perforated panels that are removable for access and cleaning reduces whole-system downtime and speeds inspections. See a practical example of such a system here: perforated panels designed for drainage and inspection access.

Be explicit in the scope: retrofit is not always “replace with something stronger” — it is replace with a system whose failure modes align with operational reality (chemicals, solids load, foot traffic, maintenance limits).

Human factors and operational rules that interact with design

Even the best design can be undermined by misuse: carrying loads that obscure footing, bypassing handrails, or using temporary covers that trap liquids. The engineering view is to design for the likely—not the ideal—use case. If workers regularly move wheeled carts along a walkway, specify edge profiles and opening patterns that avoid wheel jamming and do not rely on thin raised studs alone for grip.

Operational mitigations (training, signage) are valid, but they should be treated as complementary to design fixes rather than primary controls when hazard recurrence is high.

A practical checklist for field assessment and specification decisions (engineer’s quick guide)

- Identify whether the hazard is persistent or intermittent.

- Measure incidence frequency and consequence (near miss/injury/downtime).

- Inspect for pooled liquid, embedded solids, glazed surfaces, and level changes.

- If persistent, evaluate drainage capacity and option for open-area walking surfaces.

- Decide: short-term patch + monitoring, or planned retrofit with modular panels that allow drainage and inspection access.

- Specify inspection cadence post-change and the metric that will show success (e.g., “no pooling observed in 90 days”).

Closing: document the judgment and monitor outcomes

Every decision should carry a documented hypothesis (why this change should reduce risk), a measurement plan (what to inspect, how often), and a stop-gap action if risk increases during implementation. That engineering habit — hypothesize, implement, measure — moves a facility from reactive housekeeping to resilient design.